The principle character in this fascinating story is Josiah Austin (1746-1825) of Salem, Massachusetts, who was at various times in his career a chair maker, a cabinet-maker, and a joiner. He was the son of master carver John Austin (1718-1775) and Mary Phillips (1724-1782) of Charlestown, Massachusetts. Josiah learned the wood-working trade from his father and by 1779 had entered into a partnership with cabinet-makers Elijah Sanderson (1751-1825) and his younger brother Jacob Sanderson (1757-1810). The establishment of the Sanderson-Austin partnership in 1779 was “a watershed in the development of Salem’s furniture export trade. The firm employed many cabinetmakers, journeymen, and apprentices, as well as carvers, gilders, turners, and upholsterers on a piecework basis. They sent large shipments of furniture on speculation to the southern states, the East and West Indies, the Madeiras, South America, Africa, and more distant ports, including those in India. Not surprisingly, the names of all three men appear at the top of the list of the founding members of the Salem Cabinet-Maker Society, a clear indication of the central role they must have played in forming that organization.” [Source]

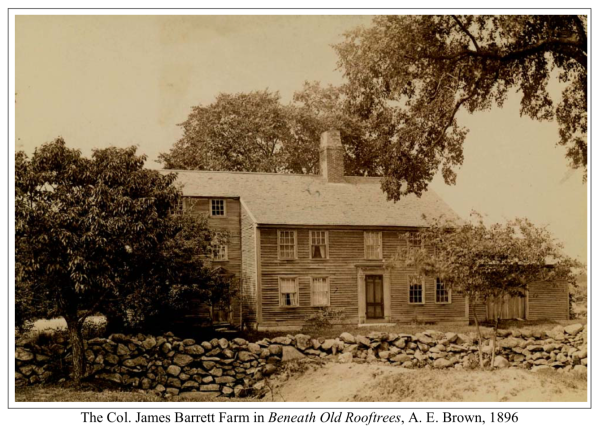

The handwritten account of the 19 April 1775 day’s events from the perspective of Josiah Austin is not dated but I would conjecture that it was recorded sometime around 1800, if not sooner though there is a possibility that it dates to as late as Josiah’s death in 1825. It appears to be the documentation of the story of Josiah’s experience for posterity, perhaps someone’s attempt to gather anecdotes for a book pertaining to the American Revolution. The particulars in the story appear to be factual. Colonel James Barrett (1710-1779) was indeed an officer in the Massachusetts militia and his farm in Concord—two miles from the North Bridge—was the storage site of all the gunpowder and weapons used by the local militia. On the morning of April 19, 1775, General Thomas Gage of the British Regulars was ordered to march the 20 miles from Boston to Concord and seize the ammunition including two cannon that were reported to be there. The story about the Colonel’s son, Stephen, also appears to be true.

A book published in 1925 entitled, “The Day of Concord and Lexington” by Allen French records that when the light infantry under Captain Parson’s command arrived at Colonel Barrett’s house, they did not find the munitions they sought. “With the warning that they had, the Barretts must have carried away a good deal of the movable stores. Emerson says that they were ‘happily secured’ just before the troops arrived ‘by Transport into ye Woods and other by-Places.’ It is said that in the garret were musket balls, flints, and even cartridges, which for concealment had been put in casks and covered with feathers. The search cannot have been very thorough for these were not found. So far as is known, the British found only some cannon carriages…”

TRANSCRIPTION

Mr. Josiah Austin, formerly of Charlestown now of Salem, Massachusetts, relates that he was at Concord with Col. [James] Barrett and others on the 18th of April 1775 having in charge ammunition &c., [and] that at midnight they received intelligence of the approach of the British regulars. The powder & balls were immediately put into wagons & sent off in different directions, & he was entrusted with one of them having for a driver a young man, son of Col. Barrett.

As he drove toward Lexington, the British army were seen descending a hill about one mile distance. The young man being terrified, proposed to take off the horse from the team and escape for their lives. Mr. Austin endeavored to dissuade him from the measure, telling him of the certain loss of ammunition which would follow, but the young man could not be prevailed on to proceed and taking off the horse, he jumped on him & was immediately out of sight.

Mr. Austin—being now left with but one yoke of young oxen and he not being used to drive a team, found it impossible to proceed with his load. At this juncture, a farmer was driving in great haste from the approaching army, Mr. Austin importuned with this man in the most earnest manner to take off his team and to assist him in securing the ammunition wagon. The farmer resolutely refused saying that the Regulars were hard by and that he should lose his team & perhaps his life. Mr. Austin replied to him that his team was of but little consequence in comparison with the ammunition wagon, that there would probably be an engagement, and that our army could do nothing without it.

Mr. Austin had the good fortune to succeed. A pair of horses was immediately attached to the wagon, a few rods from which there was a cart-way which led into the woods where they had scarcely drove ten rods when the Pioneers of the British Army came by, and seeing the farmer’s team in the road, they put their shoulders to it and shoved it to the side of the way. Mr. Austin & the farmer stood by their trust, in sight of the Regulars, and were not molested. They probably supposed them to be some affrightened “Yankees,” returning from market.

After the army had marched by, Mr. Austin and his friend drove farther into the woods to place of security and the farmer was directed to go & report Mr. Austin’s situation to Major Buttrick ¹ who ordered some of our men with saddle bags to the wagon and Mr. Austin served out the cartridges in that manner to our soldiers.

The young man ² that left Mr. Austin had rode on to Concord and reported that he had but just escaped with his life, that he looked back & saw the British cut down Austin with their broad swords. Mr. Austin returned back to Concord the next night where his friends were almost frantic with joy on seeing him alive and having saved the treasure committed to his charge.

¹ Major John Buttrick of the Concord Militia is the man who ordered “the shot heard around the world” at Concord’s North Bridge. [See John Buttrick]

² From French’s book (p. 180), previously cited, we learn that “Barrett’s son Stephen, blundering into the house [while the British were there], was mistaken for his father and arrested. The officers said, ‘You must come along with us to Boston,” but when Mrs. Barrett told them that he was her son, they released him.” Since the story does not mention which of Col. Barrett’s sons abandoned Josiah Austin, we might assume from this story that it was Stephen Barrett (1750-1824), who would have been 25 years old at the time of the event described. The ages and activities of two older brothers do not square with the story.

Where is the original of this document held? I’d like to know a little more about it’s provenance!

LikeLike

This document came to me for transcription the same as most all others sent me (to the best of my recollection). Most letters and diaries are sent to me by one or two dealers who buy and sell on eBay. They ask for a transcription and a bit of research to determine who wrote the letters and historical significance, if any. I believe I transcribed this letter about four or more years ago so I’m sure the dealer sold it shortly after my having published it on Spared & Shared. I have no idea where it is today.

LikeLike