Alfred Washington Ellet (1820-1895) was born at Penn’s Manor Bucks County, Pennsylvania on the banks of the Delaware River and was the youngest of six sons and the second youngest of fourteen children. In 1824, his family moved to Philadelphia where he attended the public schools. At age 16, he went to Bunker Hill, Illinois to take up farming.

A farmer and dry goods store owner, he was a resident of Illinois when the Civil War broke out. In August 1861, Ellet was commissioned a captain in the 9th Missouri Volunteer Infantry Regiment, which later became the 59th Illinois Volunteer Infantry Regiment. In March 1862, he fought in the Battle of Pea Ridge. When his elder brother, Col. Charles Ellet, Jr., undertook the conversion of several river steamers to rams in the spring of 1862, Alfred Ellet became lieutenant colonel of Charles Ellet’s U.S. Ram Fleet.

Following Charles Ellet’s death in June 1862, Alfred took over the unit and was appointed brigadier general of the newly formed Mississippi Ram Fleet and Marine Brigade the following November. This brigade was the only independent volunteer command in the service. It was a part of the army and not of the navy, and as such was amenable directly to the Secretary of War, and in consequence every commissioned officer in it was appointed directly by the President and the Secretary of War instead of the governors of the states. It proved to be “a most effective force in clearing the Mississippi River, and thus played a very important part n winning the war for the Union. The outstanding feature of its accomplishments was due to the bold intrepidity of its commanding general, who, in point of fearless courage, had no superior. Another thing which contributed to his success, was the fact that he was heart and soul in the cause against slavery and for the preservation of the Union. At times General Ellet seemed to act rashly; but his rashness was a failing which leaned to virtue. He was a man of strong moral conviction and character.”

Alfred commanded the Mississippi Marine Brigade during operations on the Western Rivers until 1864, when the unit was disestablished. He resigned his commission late in that year to return to civilian life.

Following the Civil War, Ellet was a businessman and civic leader in El Dorado, Kansas, where he died. He was married to Sarah Jane Roberts (1818-1875) and it was to her that all but one of these letters were addressed (one was written to his ten year-old daughter “Ellie”). There are also frequent references to his son, Edward (“Eddie”) Carpenter Ellet (1845-1922) who served with Alfred in the Ram Fleet for a time.

[Editor’s Note: These twelve letters were all penned by Alfred W. Ellet during the month of August, not long after taking over command of the Ram Fleet following the death of his brother, Charles R. Ellet, Jr. (1010-1862), who formerly commanded the fleet. They were also written just after his fleet’s participation in the attack on the Rebel iron-clad Arkansas (22 July 1862) that Alfred frequently referred to as “the monster.” The letters were part of a larger collection once owned by Matthew Miller who made the scanned images available to me for transcription and authorized me to post them on Spared & Shared.]

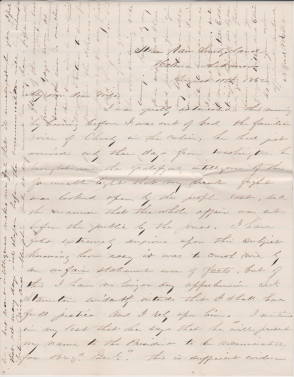

TRANSCRIPTION LETTER ONE

Steam Ram Switzerland

Helena, Arkansas

August 1st 1862

My dear wife,

I have been so busy that I have had no time to add a line to my letter and now the mail is just ready to start. I am very well and so also is Eddy. We arrived here last night—the health of our crew somewhat improved. I visited this morning General [Samuel R.] Curtis who gave me a most cordial reception. He said that he had heard of me frequently and was proud to shake me by the hand. The old gentleman was very much dissatisfied about our retrograde movement, and said that it would take the country greatly by surprise. I asked him if he knew that all the forces but ours had been ordered away by the department. He seemed astonished. If they wish us to go there and die, we can do it. But I would far rather die striking a blow for my country’s safety.

I found Mr. Brooks here with plenty of stores for my fleet so that now we will live again. I am besieged with applications to join my command. The ram fleet still has a good reputation. It will go hard with me if I do not sustain it. I am now writing to the Secretary of War for one ironclad gunboat to be added to my fleet. I want it to be a strong, well-protected, heavily-armed ram & gunboat. If I can get it, I can then get without any cooperation from those Navy men who are too slow for me in every respect.

I must now close. Give dear Ella a great deal of love for me. Tell the children to be good and obedient and kiss them both for dear Pa. Tell Edward that I wrote him a long letter about a week since. Ever truly your devoted husband, — Alfred W. Ellet

TRANSCRIPTION LETTER TWO

Steam Ram Switzerland

Helena, Arkansas

August 3d, 1862

My dear wife,

In a great hurry, I will endeavor to write to you a few lines by Eddie who I have determined to send up on a short visit home, thus separating myself from the last fond tie of kindred and affection from all. It is no small trial to me to part from Eddie who has stood so firmly by me throughout such disparate adventures. His example has been one that might well be emulated by the strongest men. Yesterday he was taken very sick with high fever and was very much out of his head nearly all night. This morning he seems much better, yet weak. I can hardly bare to part with him, but feel now that I must. We have slept together for some times past and often in his dreams, I have had him jerk me “I will take care Pa, there it comes” trying to get me out of the danger, and showing by the utmost solicitude how entirely he forgot his own danger in his attempt to protect me. I feel very fearful that he is going to be right sick yet but hope that I may be mistaken and that you may see him in all his beauty and fullness of health. I wish that you could have seen him as he stood on that deck firing his pistol into the port of the rebel monster. Few men ever did a deed so daring yet so cooley. After firing five times, one barrel stopped. He stepped to my side, took a fresh cap from out of my pocket, capped the pistol and deliberately fired his last change into the open port as we were passing. Show me an act of cooler self-possession if you can. I shall let Eddie remain as long as you think his health requires. I desire to avoid exposing him if possible to the sickness and intense heat of August and first weeks of September. I dread his being away and yet I fear to keep him. May God protect and preserve him as an honor to his country, and a comfort and pride to his parents.

I have this moment received notice that General [Samuel R.] Curtis was coming to see me. I am too much occupied to write a long letter but sincerely hope that you are not so worn down as I am just now getting ready to have the boats leave as soon as possible for Cairo and Memphis. Eddie will take what money I have received for your use—six hundred dollars. It will pay everything that is pressing upon you now and buy what you require for your comfort. I want you without fail to get you some kind of a light buggy for your own use. Pay two hundred dollars to Switzer and get my note in Alton. Make Hetzel take $125 for my note of 150 due 1st of January if you can and use the balance to suit yourself. I can for the future send you $200 per month, I think, regularly.

I was sent for to meet General Curtis on the flag ship Benton and find that a movement is contemplated shortly in which I shall participate against the guerrilla band below &c. I have not told Eddie for I know that he would object to going home if he supposed there was a likelihood of a lively time. Have no fear for me. My fate is not in my own nor your keeping. A greater being will watch over it.

I must now close. Goodbye my dear, dear wife. I hope that Eddy may get home safe and find you all well. And I know how happy you will all be to see the brave boy. Oh! how I wish that I too could step in upon you as unexpectedly and receive and deliver a share of the hugs and kisses that will be showered upon him. James is with us. Dr. Laurence still quite sick. A great deal of sickness still prevails on the fleets. Curtis & Davis have just left of Cairo to communicate with the department for the authority to corporate together for the purpose of opening this river. If they succeed, I shall have an important duty assigned to me no doubt. Goodbye. Give a great deal of love to Ma who Eddy is authorized to load with kisses and affection from me.

As ever truly your husband, — Alfred W. Ellet.

TRANSCRIPTION LETTER THREE

Steam Ram Switzerland

Helena, Arkansas

August 4th 1862

My own dear Wife,

After a day of unusual pleasure, evening finds me at my old occupation of writing to my loved one. Eddie left me yesterday and before you can possibility receive this letter—if he meets with no detention—he will be with you. Oh, how I wish that I could make me of your happy party. I hope you will inform me immediately upon his arrival so that I may know of his safety.

I started down the river at the same moment that he started up. He can tell you how busy I was during the day. I concluded to go down to the camp of the 33d [Illinois Infantry] and visit cousin Charley [Ellet] Lippincott, about twenty miles below. I got there just at dark [and] found that Charley was up north on business and not expected back for a couple of weeks. I ordered the Sampson to remain opposite Colonel Hovey’s camp on picket duty to assist their Colonel in any undertaking against the enemy, and in capturing some contraband cotton that he had found and then returned on the Fulton to the fleet. Colonel Hovey is camped on the plantation of the famous [Col.] Matt[hew F.] Ward.

This morning I was wakened by a man with heavy, sandy whiskers & mustache and bushy head of light hair coming into my room unceremoniously thrusting his hand under the mosquito bar with, “Good morning, Colonel. But I believe you don’t know me.” It was cousin Charley Lippincott. I was soon dressed and he spent the day with me and has but just gone down on one of my boats to his regiment. I have passed the pleasantest day that I have experienced since our great sorrow. The memory of the old days of Plainview were all revived and things that I had long since forgotten were again remembered and laughed heartily over. A few hours after Charley came, I had another arrival of Bartlett and the boys. They came down on the City of Alton and I enjoyed another great treat in your long and interesting letter—also dear Ma and Edward’s, besides cousin Thomas Lippincotts’ and all the others. Was not all this opportune to prevent my feeling low-spirited at parting with Eddie?

The carpet sack came safe to hand with the shirts and other contents. The shirts are admirable having both length and breadth, two qualifications that are indispensable from me in shirts. The bible I will keep for Eddie’s return. It was very kind in the doctor to send it to him. I was much pleased with Mr. Thomas’ biography on my brother [Col. Charles Ellet] and will save the posts for Eddy also. It was always his favorite paper. I do not fear with Aunt Hannah that there is any danger of Mary’s following in the disloyal course of her mother’s family. She is too proud of her father and of his reputation to ever blot it by any disloyal act on her part.

Regarding the attempts to burn the Monarch, I have never had a report yet. I have heard the rumor but I have had no time yet to inquire into it. I have no doubt however that it was attempted by some of the cowardly villains who afraid that they could not get a discharge took this means to get themselves far from their six month obligation.

General [Samuel R.] Curtis & Flag Officer [Charles Henry] Davis have both gone to Cairo to communicate directly with the department to obtain authority to act in concert on this river to open it immediately by a combined movement to the Gulf. They sent for me before starting and gave me their plans which of course must not be spoken of. They both complimented me and said that they would hope to obtain my aid, &c. &c. which of course they shall have in any and all ways that I can assist. I think that nothing is so important as to open this river and nothing much easier to be done if we can only procure some concert of action. Vicksburg can be taken in two hours if they would only do as I proposed near a month ago to [Admirals] Farragut & Davis. Let these gunboats be pushed right up to the batteries at close quarters and silence them with grape and canister. Their guns are all exposed. And I will engage to land five hundred men and passing under our own fire, spike every gun before the enemy could know what I intended. Our boats would of course elevate their guns as I approached the forts so that their fire would still pass over me and fall so as to prevent the enemy from advancing from behind. This thing could be accomplished so quick, commencing at the upper fort and taking them in succession that it seems strange that it has not been accomplished. I have talked with Davis repeatedly about it but he fears to bring his boats to close quarters. [As] for myself, I want to see more close quarters fighting. We have stood off from these villains long enough and now I want to see them “crowded to the wall.” There are no open fair enemies but secret villains who lurk in ambush to take some brave men who they are too cowardly to attack openly unprepared and shoot him under cover or from ambush. I tell you that all that high falutin idea of southern chivalry is played out entirely with me. I have had too many balls whistle by my ears aimed by some lurking villain who took good care to keep out of sight for me to entertain any longer any refined notion about the way of carrying on this war. I am now for crushing out this rebellion if with it the life of every traitor, man, woman and child in the South should be made a sacrifice of, and the whole country made a desert waste. Let us fight the thing out with clean hands and without gloves.

TRANSCRIPTION LETTER FOUR

Helena, Arkansas

August 5th 1862

My dear Wife,

I have just had a visit from Captain Phelps, at present commanding the gun boats during [Admiral Charles Henry] Davis’ temporary absence, and have arranged for a trip down to the mouth of White River and below. Yesterday a party of several hundred of General [Samuel R.] Curtis’ command were surprised by a party of the enemy and badly cut up and a large forage train captured. General [Frederick] Steele has sent out a large force of cavalry to try to overtake the Rebels and is intending to send one or two thousand men up White River by transports to get in on the rear of these scoundrels. The gunboat Louisville is to convoy the transports and the rams to protect the whole. I do not intend to enter White River but will watch at its mouth and probably drop down fifty miles or so further to see if the Rebels are at work fortifying at all. This is only a little movement and I expect to get back in three or four days though may be detained for a week, so that you must not think it singular if you get no letters for some time. I will write always whenever I have an opportunity for getting my letter off.

I was greatly amused at Orpheus Kerr’s ¹ letter on the escape of the Arkansas. I would like to send it to [Admiral] Davis but will not as I desire to maintain the best possible relationship between the fleets, such as at present exists. We can act now effectively. They will always hereafter support me, and stand by me, for their own existence would be forfeited if they did not. The people would not permit another such a failure on their parts, and Davis has been taught to know that he may implicitly trust me. I shall therefore studiously avoid anything that might tend to effect this relationship. I wish that I could tell you many things that have occurred to exhibit how I have fought my way into the good opinion of men determined to dislike me, and who would have hated me if they dared, but who now find it difficult to my face to flatter me too much. Don’t suppose that I shall be made a fool of by these things, dear Sarah, but I will not deny to you that I feel a pride within me as being able to hold these peoples outward respect, even if it is produced by fear.

If you can procure the New York Herald, Cincinnati Gazette, New York Tribune or Chicago Tribune, you will find a fair account of my last engagement. At least I know that reporters had the opportunity of obtaining all the facts and did know all about the fight, and the previous agreements. I believe they are fair men and will tell a true story. I observe that the St. Louis papers have avoided giving my name so that I hope you did not know of my danger until you got my letter informing you of my safety.

In sending Eddie off day before yesterday, I forgot to tell you to give John for me a present of $10.00. He is doing I know as well as he can by himself and must have had a right lonely time of it. Tell him not to get discouraged but when old Morgan makes him mad, to think of me and Vicksburg, and he will soon get in good humor. I shall be right glad to see him and shake his honest hand once more. Tell him that I have every confidence in him and have no fear but that my interest is well cared for in his hands. I have to trust it all to him for I cannot think of any other business matters than those connected with my fleet.

And now again goodbye with love to all. “Bushels” to dear Ma, as ever.

Yours truly and only, — Alfred W. Ellet

¹ Robert Henry Newell (1836-1901) wrote a series of satirical articles during the Civil War using the pseudonym Orpheus C. Kerr, commenting on the war and contemporary society. His articles appeared weekly in the New York Sunday Mercury, where he was the literary editor until 1862. From ~1862–65, he was married to famous actress Adah Isaacs Menken. The name “Orpheus C. Kerr” was a play on the term “office seeker.” At the time, political offices were seen as plums, involving relatively little work and regular pay, and were used by political parties as rewards for faithful party workers. During the war, the Orpheus C. Kerr Papers was widely read and Newell enjoyed great popularity. He was one of the favorite humorists of Abraham Lincoln. When General Montgomery C. Meigs admitted that he had never heard of Orpheus C. Kerr or his Papers, Lincoln responded, “anyone who has not read them is a heathen.” [Wikipedia]

TRANSCRIPTION LETTER FIVE

Steam Ram Switzerland

Helena, Arkansas

August 8th 1862

My dear Wife,

I returned last night after a fruitless trip of over two hundred miles. We went a little below Napoleon at the mouth of the Arkansas river but found no enemy, nor any sight of one. The expedition up White river was a failure for want of water. The boats found upon entering the mouth of the river that it would not be safe to attempt to go up it, and so the whole expedition was a failure and we started upon our return. The gunboats were so slow that I pushed on ahead after accompanying them about forty miles and arrived here last evening. We are looking now momentarily for the return of the balance of the boats. I left the Monarch in command of Wheel to protect the return of the boats.

I was disappointed upon arriving here to find no letters. There has been no mail down since we left. There surely will ba a boat down during the day. It is time for General [Samuel R.] Curtis & [Admiral Charles Henry] Davis to return. I desire very much for them to return so that I may know what the future is to be. I hope that all of Curtis’ army and our fleet may be sent to Vicksburg and reduce that place and from thence onwards until this river is indisputably in our possession from its mouth to its source. There should be no delay about this. What is Little Rock or the entire State of Arkansas compared to the possession of this river? And yet they have received marching orders, it is reported, to go to Little Rock.

James is not well today. He has been complaining since morning with sick stomach. I do not think it will amount to anything, as he seems better than he was yesterday and has just eaten a good large saucer of canned peaches. The Lancaster nor Lioness have neither of them returned from Memphis. I expected them both before now. I have a good deal of writing before the mail leaves and must now close. I trust that Eddie is home before this. Give a great deal of love to Ma and Edward and all my friends.

Always your own husband, — Alfred W. Ellet

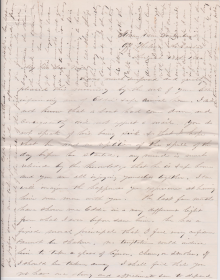

TRANSCRIPTION LETTER SIX

Steam Ram Switzerland

Helena, Arkansas

August 10th 1862

My own dear wife,

I was greatly astonished this morning by hearing before I was out of bed the familiar voice of Charley in the cabin. He had just arrived only three days from Washington. He brought me the gratifying intelligence of the favorable light that my recent fight was looked upon by the people East, and the manner that the whole affair was set before the public by the press. I have felt extremely anxious upon this subject knowing how easy it was to crush me by an unfair statement even of facts, but of this I have no longer any apprehension. Secretary Stanton evidently intends that I shall have full justice and I rely upon him. I mentioned in my last that he says that he “will present my name to the President to be nominated for Brigadier General.” This is sufficient evidence that he does not blame me for the late failure.

I have just received and read with eyes overflowing all your kind letters in answer to mine respecting this Arkansas matter. You cannot imagine the strength it gives me to read those dear testimonials of your love and confidence. I shall continue to try to get so that I may always merit your love and praise. Dear Ma’s letter and Edward’s are all dear to me, showing how confidently they rely upon my doing my duty. I do not want you to express the feelings to others that your letters exhibits towards the commander in writing to me. I have fought my way into a position that I have nothing to fear from them, and the country has everything to gain from the knowledge that a cordial state of feelings exist between the commanders of the two fleets. They will never desert me again. Indeed, I know that it is a deep set principle with them all to find some chance by protecting me to wipe out what they are now stigmatized with—bare desertion. Then do not let your indignation carry you too far. I do not think that there was any intention to sacrifice me, but believe that it all was the effect of gross carelessness being entirely indifferent as to what was my fate, and at the same time warm regard for their own safety. I firmly believe that they had all so thoroughly convinced themselves that I could not escape, that they did not think it worthwhile to even look after me. If I had been killed, the world would never have known under what agreement I undertook that desperate adventure and I should have been derided as a hair-brained fool and madman.

I hope that Eddie has got safely home and is well. I want him to enjoy his visit and will let him stay as long as he desires. I miss him greatly and should more if I was expecting to go into any perilous enterprise. His cool courage in the hour of greatest danger affords me great support. The influence is so great upon the men. I have promoted Granville to 2nd Engineer and he gets now $100. He is one of the “bravest of the brave.” Most fortunately I have some men upon whom I can implicitly rely. I wish there was more of them.

[Editor’s note: The fourth page of this letter is missing from the file so I cannot vouch for the accuracy of the following two paragraphs. The final paragraph is accurate, as it was written in the margin of the first page.]

Charley ¹ will now remain with me. I shall place him in command of the Queen [of the West] as soon as she returns. I have already put Bartlett in command of the Monarch so that there I will have somebody upon whom I can count for support. That will give me three boats upon which I can rely. My own, Charley, and Bartlett’s, either of whom will stand by me to the death. I must now close. I have not yet received the Secretary of War anything to increase my force. I am sending him another telegraph today upon that subject.

I want to get Phil Howard, Isaac Newell, and many others who want to join me. I read another letter from Charley Adams desiring also to get under my command. I had answered his former letter but had not sent it. I fear on acts of his family to bring Charley, even if I obtain the set authorizing to do so. My position must necessarily be one of unusual peril and I hesitate on account of Charley’s mother to be instrumental in putting him in like danger. I should be glad to have him for his kind confidence in me is very flattering and I am much attached to him. I had almost, my dear wife, made up my mind to write to you to come down and pay me a short visit while we remain here. I am most anxious to see you and tell you all my thoughts, hopes, and fears, and to clasp you once more to my throbbing heart. Oh what a happiness it would be, but recent intelligence makes me feel that it must not be yet.

I feel that not many days will elapse before the communication will be interrupted between Cairo and Memphis, and at any moment we may have a fight with a fleet of the enemy boats from the Yazoo River. As soon as the river is once clear so that there will be no special danger, I intend to send for you, but the Arkansas must be put out of the way first and the power on this river of our government be overwhelming to the enemy. Goodbye my dear wife, God bless and preserve you. Give my love to dear Ma and tell her that I will write to her as soon as I can get leisure. Write to me often. Tell Eddie to enjoy himself all he can and give him also fathers love, nor must you forget Willie and Ellie.

As ever, your affectionate husband, — Alfred W. Ellet

¹ Charles (“Charley”) Rivers Ellet (1843-1863) was the son of Charles Ellet, Jr. who established the U. S. Ram Fleet in the spring of 1862. Charley was a medical student when the war began and served as an Asst. Surgeon until he was transferred to the Ram Fleet and promoted to the rank of Colonel. He was placed in command of the ram Queen of the West during her daring independent operations below Vicksburg in February 1863. He commanded the ram Switzerland when she steamed past the Vicksburg fortification in March 1863. He died of illness in late October 1863.

TRANSCRIPTION LETTER SEVEN

Steam Ram Switzerland

Off Helena, Arkansas

August 11th 1862

My own dear Wife,

Your letter of the 7th and Edward’s of the 8th I found on my table this evening upon my return from taking tea with Captain [Seth Ledyard] Phelps and some of his officers, by invitation brought by himself in person and coming for me in his tug. I was very sorry to hear that my dear little Ellie is sick and I cannot come to her. These are my severest moments of trial to know that any of my dear family is sick and as liking for father, and yet I cannot come. Dear Ellie, I hope that she is long since well. Father would come to see his dear little daughter without urging if he could, but I cannot desert my post. If any of you should sicken and die, God alone knows what would become of me. My heart would break if I could not be with you. Take care of yourself and the children, my dear wife. Try to keep them from exposing themselves and let us pray that if we are ever permitted to meet again, that we may meet as of old with the same happy faces to surround us. Kiss the dear child for me and tell her that father thinks of her by day and night. I wrote you a long letter my dear wife this morning but hearing of Ellie’s sickness, I cannot sleep and must write again.

Captain [Seth L.] Phelps informed this evening that [Admiral Charles Henry] “Davis has been assigned to another department” and he does not know who is to be his successor on the Mississippi. I suspect that late matters have had something to do with the change. Phelps has been more than ever very courteous to me this evening. He came to see me immediately after receiving his mail and before my own had been distributed. There is something in the wind that I do not yet see clearly. He very kindly suggested to me the importance it would be to my command to adopt a naval organization and showed me how readily it could be accomplished by asking the favor of the Secretary of War. There was some things also that escaped him respecting the fine gunboat & ram Eastport that interested me greatly but which I failed to let him see. The Eastport has been his hobby for some time past. She is said to be by far the best boat on the river. He has repeatedly told me that he was to command her and she was to be the flag ship. Today he damned the Eastport and did not care who commanded her, if he was to have a new and untried flag officer. I could not help feeling a thrill and a hope that perhaps she might have changed her direction and that I may get her. I would give almost everything to command her with a good and trusty crew, if only for one or two weeks. You should hear from me soon, I pledge you my word. I am very deserving for one good effective boat. Give me the Eastport and I will pledge my life to clear this river of every hostile craft in ten days after she is manned and armed. It is a lasting disgrace—a sin—and shame that the whole of rebeldom should be permitted to exalt over our supposed retreat. If I could have that boat, they should soon have another page written for the history of this cursed rebellion.

I think very soon a move will be made by us all to Vicksburg. Today’s news all seems to point in that direction—nothing definitive, but much rumor. One transport came down this evening late bringing the intelligence that fifty or sixty more would follow in the next three or four days, as fast as they can be chartered by the government agents. This can have no other meaning than to move [Gen. Samuel R.] Curtis and whole Army to Vicksburg.

I read a letter from Henry Gildemeister this evening informing me of his promotion to lieutenant of a new calvary regiment [1st Missouri Cavalry]. I am right glad to hear this and believe Henry will make a good officer. He is a true man and God knows they are scarce at this time of general depravity. Be sure when next you see any member of the family, to give them my kindness regards and congratulations upon Henry’s well deserved promotion. I also read a very kind and characterized letter from Russell Scarritt congratulating me upon my fortunate escape &c. &c. Also one from James B. Clark which I have answered.

Tell Edward that cousin Charley’s [Charles R. Ellet] prospects for promotion are too good for him to leave his present post. He will be colonel as soon as [Alvin P.] Hovey is made Brigadier [General], which must be very soon. You asked me what my rank is, Lt. Colonel Commanding, giving me a Colonel’s pay. If the Honorable Secretary of War does not “forget” his promise, I shall make one of the fastest promotion of the war. I think that he will do what he promises but I will freely relinquish my claim to be permitted to command the Eastport for two weeks. I don’t plan to capture that Arkansas. I can do it as sure and as safely as you can do a sum in plain addition if I could only for a few days have command of a good boat. Is it not too bad to be so hampered? My boats are not capable of contending against this monster except at fearful odds against them. The Secretary ought to give me one efficient boat. I ask no more. Goodbye, my dear, dear wife. Give Ma a great deal of love from me and remember me as ever, your husband, truly yours, — Alfred W. Ellet

TRANSCRIPTION LETTER EIGHT

Steam Ram Switzerland

Off Helena, Arkansas

August 13th 1862

My own dear wife,

I was much surprised and greatly pleased this morning by the receipt of your letter informing me of Eddie’s safe arrival home. I did not know that a boat had come down and consequently did not expect a mail. You do not speak of his being sick so that I hope that he had no repetition of the spell of the day before he started. My mind is much relieved by the knowledge that he is safe home and you are all enjoying yourselves together. I can well imagine the happiness you experience at having him once more with you. The last few months have shown me Eddie in a very different light from what I ever before saw him. He has a fixed moral principal that I feel every confidence cannot be shaken. No temptation could induce him to take a glass of liquor, chew, or smoke. If I should be taken away, I shall feel that you yet have one strong and affectionate son to depend upon. I have unlimited confidence in him.

I feel very sorry to hear of Ellie’s continued illness. Does pleurisy usually continue so long to produce pain, or is it some trouble of her lungs that is causing this sickness? Do get well, dear Ellie, right soon. And let me know that you are all able to enjoy Eddie’s society while he is at home and contribute to his pleasure while he can stay with you. I am very desirous to hear what Ma thinks of him, his appearance, and manners.

I have been having Charley Lippincott visiting me all day. I went down to see Colonel Hovey and consult with him about an expedition down the river last night and Charley returned with me. We sat up very late last night and all day we have talked over incidents and occurrences at Plainview. We passed a very pleasant day and he has just left. James went down with him on the Fulton to visit the sick on the Monarch. She is down opposite their camp on picket duty and acting as a guard to the camp at the river. Charley is not changed at all. He is the same improvident, reckless fellow that you knew sixteen or seventeen years ago. He is ambitious and aspiring, and popular amongst his men and officers. He is very brave and of course is successful in all his expeditions. He desires me to be sure when next I wrote, to give you and Aunt Mary and Cousin Edward a great deal of love from him, and has promised to write to Edward when he could stir up a writing humor.

One little incident will show you Charley as he always was. Upon one occasion, his little command of one hundred men was sent out upon a special expedition to guard some bridges. He left fifty to look after the bridges while with the others he went to hunt up the enemy— Jeff Thomson’s command. He found him very unexpectedly in ambush and the first notice was a volley of musketry from the woods. Charley and his men being on the railroad track, every man in fair sight. Only one was wounded. He and his men took cover and fought a force of four hundred for three quarters of an hour. Finally he was obliged to retract, but in making off the field, the enemy had closed around them and it became a hand-to-hand fight. Seeing one of his men attacked by two of Thomson’s men on the opposite of a fence, Charley thought that was not fair play and jumped the fence and rushed in, striking at one of them, hit him over the shoulder without hurting him any. The fellow ran and Charley after him. As the fugitive reached the fence, he threw himself across it, but Charley’s sword reached his hinder extremity and was well thrust in. The fellow howled and made such extravagant gesture of alarm and pain that Charley had to stop and have a laugh. When looking round, he observed his comrade had his man, holding him at musket length with the bayonet through the fellow’s neck. The fellow was squealing at such a rate that Charley became at once convulsed with scarcely power to do anything.

Just at this moment, a captain of the enemy came rushing at him, pistol in hand. Charley ran at him, the Captain fired but missed, and Charley failed to run him through—the blade glancing by the fellow’s side. However, he knocked the captain down and went to work to butcher him. He gouged him all over the breast with his sword but could not get through the fellow’s thick clothing. Finally while busily engaged trying to find the tender spot, some six or seven of the captain’s men came up. Charley had succeeded in getting his [the captain’s] pistol away from him. He found he must leave and had not yet hurt the fellow. He started to run when the captain jumped up and called out to his men to shoot the damned Yankee. Charley said that that reminded him that he might as well shoot too, so he stopped and turned round, and shot the Captain dead with his own pistol.

He lost in the fight seven men taken prisoner who were afterwards exchanged from whom he learned much of the results of the fight. The fellow who had bayonetted the other in the neck was taken a prisoner. He could not get his bayonet loose and he would not give it up to lose it, so was taken as a prisoner. It is most amusing to hear Charley tell these things in his way, seeing something to laugh at all the way along as he relates his story. Both the captain and man that he stabbed in the behind died.

General [Samuel R.] Curtis nor [Admiral Charles H.] Davis have yet returned. What can keep them so long? I cannot imagine Davis will not come back, I am informed, to command. Something will be done, I feel sure, before very long. At least there will be a determination of some course of policy.

Private

Night! August 13th 1862

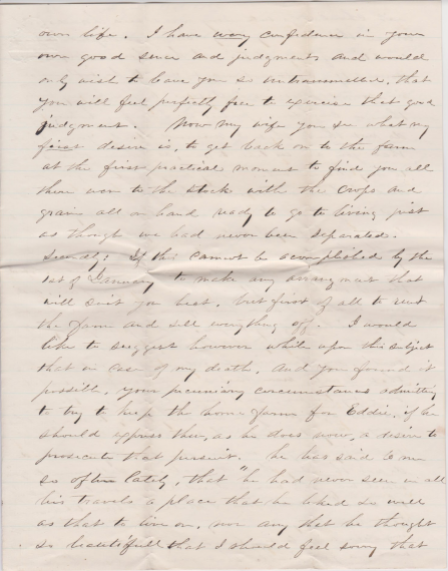

I hardly know how to advise you respecting the disposition to be made of the oats and wheat. My desire would be to retain in the barn all the grain and sell nothing until the 1st of January, before which time I shall know what to do with our farm. If, however, you would prefer not to remain any longer on the place, and can possibly rent it now, I shall offer no objections. Indeed, will cordially give my consent and there would prefer to sell all the grain, hay, and everything else. I only want to see what the fall campaign will bring about. If the rebellion is crushed and the war about to close up, these boats will have nothing further to do, and I should then feel justified in tendering my resignation even if I have the command of a Brigade. I do not feel now that I should continue to serve unless hostilities actually continued. At any rate, I don’t intend to have you remain after January on the farm without me—if I live—and wish now that all your arrangements may be made with reference to that plan. Let me know where you will prefer to go if the farm is rented, remembering that you and the children’s interest is alone to be consulted. Thank God that while I remain here, from this onward, I can furnish you with all the funds that you will ever desire to use without injury to any creditor. I have prayed for this hour and it has come.

You know that I very much wish to retain what property we yet have remaining on the farm if I can reasonably soon expect to return and live on the place. For that reason I should desire to retain the crops of this year. The horses and cattle I prize higher than probably they are worth because I know them. And it would be a pleasure to me to return to the place and find it as much as possible unchanged. My plans all center there. I look in no possible contingency to any other place. I feel that if I live, that I shall soon work myself entirely out of debt and with our farm clear, together I feel that we can live happily there. If I do not live to return, do not think that I wish to have you remain on the place. I want that thing fairly and distinctly understood by everybody—that you are to consult your own desires only. I have no wish to regulate or control your happiness or comfort beyond my own life. I have every confidence in your own good sense and judgment, and would only wish to leave you so untrammeled that you will feel perfectly free to exercise that good judgment. Now, my wife, you see what my first desire is—to get back on to the farm at the first practical moment to find you all there, even to the stock with the crops and grains, all on hand ready to go to living just as though we had never been separated.

Secondly: If this cannot be accomplished by the 1st of January, to make any arrangement that will suit you best—but first of all to rent the farm and sell everything off. I would like to suggest, however, while upon this subject that in case of my death, and you found it possible, your pecuniary circumstances admitting, to try to keep the home farm for Eddie—if he should express then, as he does now, a desire to prosecute that pursuit. He has said to me so often lately that he had never seen in all his travels a place that he liked so well as that to live on, nor any that he thought so beautiful, that I should feel sorry that it should go into anyone else’s hands. Of course this—as everything else—must depend upon the condition of my estate. I have been writing this for yourself. I do not want you to be influenced in your expression of desire to me by anybody. There is confidence—perfect confidence—between us. Do not think that I misunderstand you. I feel that you are as true to me as I know that I am to my dearest wife. My every throb is for you and I have no desires that do not begin and end in you.

Oh God, when I allow my mind to dwell in this way, I feel that my head would bust with the intense desire to clasp you once more to my breast and hold you there forever. And then I think how often I have cost you pain, and how unmanly I have hurt your dear kind heart by the violence of my temper, and I pledge myself if I can ever enjoy the blessing I must covet on earth—my dear wife’s confident and entire love—that I will ever keep a more careful watch over my temper and never cause you the same distress again. You are everything to me in this world, my dear wife. But also, I have no hope of ever enjoying you unless our country is restored. Do not then say that it makes no difference to you which way this war is decided. Remember that if the South is victorious, I shall not live to know it. I can never lay down my arms until I can clasp my dear wife to my breast with the assurance that we are a free people—that our children have a free inheritance.

Goodbye. May God bless you and the children. As ever your own and your only affectionate husband, — Alfred W. Ellet

TRANSCRIPTION LETTER NINE

August 15th [1862]

Yesterday I was down the river all day in company with Col. [Alvin P.] Hovey, about forty miles down, and did not get my letter off as I should have done by the mail of this day. Today I have received yours of the 10th inst. I am right glad to learn that Eddie is well again, and that Eddie is enjoying himself, and that your darkey is likely to prove useful. Jimmy returned to the fleet today and came near not being able to report himself although within speaking distance. He was run down by one of [Admiral] Davis’ tugs, his skiff upset, and himself and two niggers precipitated into the river. It was a careless outrage and came near causing the loss of all three lives. As it was, Jimmy succeeded in reaching the tug and climbed on her and the darkeys were picked up after some difficulty. This with Charley [Charles R. Ellet] is another cause of intensifying his hatred to the gunboats and their commander.

You have probably before this learned of the destruction of the Arkansas. I know how you will rejoice at this circumstance and for my country’s cause. I feel grateful also that so formidable a boat is out of the way but it is mixed in me with a feeling of regret that I have not the honor of destroying her. I had marked her out as my special game and was only waiting for authority to increase my force, and get my boats once more together to start once more in pursuit of her. I had intended to pursue her if I had to run the batteries at Vicksburg and follow her to the Gulf. I know that I could have captured her.

General [Samuel R.] Curtis returned yesterday but I can learn of no movement in anticipation yet. [Admiral Charles H.] Davis is said to be sick at Cairo. Capt [Seth Ledyard] Phelps was here a few minutes ago. He says that Davis be taken away very soon as he has been appointed to a Naval Bureau, and it is still not known who is to be flag officer of the squadron. Phelps is evidently looking that way himself and is now endeavoring to obtain my influence in some way to help him. I don’t see yet what he is after, but I know there is something he expects from me or he never would lavish so much attention on me in the face of all the newspaper stories that he has had the opportunities of reading lately. He comes almost every day to see me in the most familiar manner whilst I go only to see him upon business or when specially invited. All my men notice the change that has taken place towards their colonel by these people.

The Eastport I can learn nothing more about. Capt. Phelps says that he don’t know anything about her, and this to when Davis is right when she is being built and sending communications daily to Phelps. There is a mystery about us just now that I cannot clearly understand. Some think that the gunboats are to swallow up the rams, but nothing is known clearly about the matter.

[Quartermaster General] Mr. Brooks is now in Washington looking after the interest of the fleet. I sent him with letters to [Secretary] Stanton to try to procure me one first-class ironclad gunboat and ram to add to my command, and to attend to some other business. I hope to hear something before long as to our future destiny. I have now on board a correspondent of New York Times who came with letters desiring to be permitted to accompany the fleet and observe and give publicity to its bold deeds. I shall keep on this fellow right side if possible.Much depends to ensure a man’s success as to how his acts are set before the public. I am very anxious just now for further news from [General Nathaniel P.] Banks column. I hope and believe that he has destroyed Stonewall Jackson but must see it confirmed. I always had great faith in Banks.

Everything is as quiet as it could possibly be desired by the laziest man on earth about here. Charley [Charles R. Ellet] will die off, I very much fear, if we do not do something soon. He is all impatient to move. My boats do not return once they get from under my eye. It becomes a debatable question if I shall ever again see them. The Lancaster has not yet reported herself. Good & dear Sarah, give Ma a great deal of love from your ever affectionate husband, — Alfred W. Ellet

TRANSCRIPTION LETTER TEN

Steam Ram Switzerland

Mouth of Yazoo River

August 21st 1862

My own dear wife,

I will begin now the first moment of actual leisure since my last letter to dear Ma from Helena to write up for your benefit, the events of this eventful trip. We started from Helena as I mentioned in my letter to Ma almost immediately after closing and sending off my letter. I in the Switzerland, [E. W.] Bartlett in command of the Monarch, and the Sampson & Lioness to accompany us as reserve, the Benton, Mound City, and General Bragg of the gunboat flotilla, and two transports containing in all seven hundred troops. The Benton & Mound City [took] the advance, the ram fleet next, the transports behind us, and the Bragg bringing up the rear. We proceeded in this order steadily down the river without anything of importance occurring except that the Monarch unshipped her rudder and broke her tiller by running over a snag. I remained with the Switzerland until the repairs were completed when we soon overtook the fleet at Milliken’s Bend.

About twenty-five miles above Vicksburg, we came suddenly upon a steamboat lying at the shore with steam down, and on the bank above her a regiment of the enemy encamped. We at once rounded to by her side, nearly all the crew running away as we approached. Several were caught in their beds, being sound sleepers—they were not aroused by the noise. It was three o’clock in the morning. The brave Southern troops skedaddled without firing a gun, leaving everything behind—tents, camp equipage, horses, mules, wagons, harness, a good many arms in the tents—all fell into our hands and no resistance offered by an enemy twice our own strength. Our men were all day basically engaged getting this stuff on board the boats. The steamer was a valuable prize. She is a very nice small side-wheel boat, nearly new [and] loaded to the guards with all kinds of army stores. [There were] between five & six thousand new rifles, any amount of cartridge boxes, bayonets & scabbards, belts, saddles, bridles, ammunition in countless boxes, rifles & pistol cartridges, and fixed ammunition for field pieces. It was a rich haul and will be severely felt by [Thomas C.] Hindman for whose command it was destined.

After our troops returned—for they run the enemy to Richmond, a distance of eighteen miles in the interior—a railroad station, and broke up another rebel encampment on their way, burned up the railroad building &c. &c.—we all reembarked and proceeded to our old anchorage opposite the end of General Williams’ famous ditch [and] found everything just as we left it. [There was] no change on the peninsula excepting that in the fall of the Mississippi, the bottom of the ditch was about ten feet above the surface of the water. While lying here we were visited by a tremendous storm of rain and lightening which continued for several hours.

Having no further object to serve here, [Capt.] Phelps and I determined to take an excursion as far as possible up the Yazoo River. Leaving the Switzerland & Bragg—both of which boats draw too much water—at the mouth of the river to guard the transports, and taking on each of my boats 100 additional soldiers, we proceeded up the Yazoo, Benton in advance, Monarch, Sampson & Lioness next, and the Mound City bringing up the rear. We advanced in this order at close sailing distance so that all my boats were under the cover of the fire of both gunboats to Hayne’s Bluff—Eddie will have a keen recollection of the place—where we could see a number of men running up from the old mill and secreting themselves in the bushes on the sides of the hill. Fresh piles of earth work showed clearly that the oft talked of battery was there and we waited in momentary expectation of seeing the white smoke puff out and hear the rushing shot. The suspense was soon broken by the Benton sending one of her largest shells howling up the side of the hill and then the rascals showed themselves—not to fight but to run. And well they did the graceful through the cornfield, and over the hillside until they turned the brow of the hill when we saw no more of them. I have no doubt they are running yet for both boats opened fire upon them. And they did not stop in any reasonable distance I know.

We landed under the fire and found that we had got a prize again. The guns were not yet in position. Four heavy siege guns were lying by the side of their carriages, two brass field pieces, their mountings all laying close by, tons and tons of ammunition, shot, and shell in the greatest abundance, barrels and barrels of powders and quantities of “fixed” ammunition in boxes for the field piece, and 20-lb howitzers. We all went to work immediately to save what was of value to us and destroy the balance. We rolled all the solid shot into the river and the powder likewise. All the valuable prepared ammunition we took on board. The small cannon we also got on board, but we could not handle the large ones and were consequently obligated to burst them. So you see we have frustrated the little plan of this enemy for our future benefit. They must look out for more guns and another supply of ammunition before they can dispute our passage of the Yazoo at Hayne’s Bluff. Our arrival was most opportune. The guns and ammunition was only brought there two days before our arrival. Yesterday was the day fixed for all the country to turn out to aid in getting them into position. We came the day before and they will hardly think it advisable for the present to prosecute their original plans.

After accomplishing all to our satisfaction at this point, we proceeded up the river to the mouth of Sunflower where the water became so low that the gunboats nor Monarch could proceed no further with safety. I then sent the Sampson & Lioness on alone up the river the Sunflower. They proceeded about twenty miles with a good deal of difficulty but could not reach Lake George where five or six steamers are lying safe by about ten miles. It was near midnight before the two boats returned to where I was waiting for them. The gunboats had long before left to make their slow progress out of the river in advance of us. But finding that we were much longer detained and did not overtake them, they waited at the bluff to see us get by. While patiently waiting for us they were fired into from the shore and the First Lieutenant of the Benton very seriously wounded. They retaliated with several shells into the woods and were gratified with hearing that groan followed the bursting of the shell showing that the Lieutenant was quickly revenged.

We are now just starting again for Helena. We got safely out of the Yazoo and I think that you will agree with me that visit was a timely one. We have done irreparable damage to the enemy, have surprised him in every way, have broken up his calculation, disturbed his plans, carried consternation and distrust throughout his camp, for they are under the impression that our success is owing to trickery of some of their own people. All of the planters are firmly of the opinion that our visit was caused by information obtained from deserters, while in truth it was the merest accident in the world.

August 22nd. We have been steadily advancing up stream all night but have made very little progress. From late in the afternoon yesterday until midnight we have been under the most intense state of excitement. 1st, I ordered the Monarch to proceed to the coal barges that were being towed up close to the Benton some distance in advance of us. I at the time was trying to get the Bragg off a bar, she being aground. As the Monarch passed us, we discovered her to be on fire and the most intense excitement prevailed until we discovered that it was seen by her own crew and they had subdued it. Then shortly after dark, we got fast a ground with two barges in tow, and while laboring to get off, a man fell overboard. He was caught fortunately at the moment and saved. Scarcely half an hour afterwards, a negro stepped off the deck and passed under the wheel when we were in motion again, and we saw no more of him. I sent out a yawl and men and searched the water, but could find nothing of him. Would you believe that in less than half an hour after, another man while talking of the late casualty, stepped right off backward from the same spot, and me looking at him. He passed also under the wheel but escaped injury by diving and when he came to the surface, called lustily for help. I had the yawl manned as quickly as possible and had the gratification of saving his life. Yet even after all this, another man would have gone the same way if the mate had not caught hold of him, and they came near going overboard together. You can imagine how all these things unnerved me and this morning I feel exhausted and thoroughly worn out.

23rd [August 1862] Greenville, 170 miles below Helena.

The rebels had the intention of disputing our passage by this place, so we have heard from various sources. Upon our approach we could see a party under cover of the wood evidently meditating some devilment. The gunboats opened fire upon them and the way they scampered was really amusing to observe. Colonel [Charles R.] Woods‘ men are now landing, intending to scour the country around and if possible break up this nest of scoundrels. I shall leave the fleet in about an hour to proceed in advance to Helena. We unfortunately snagged our coal barge last night and lost our supply of coal. The fleet cannot get up further than Napoleon without a fresh supply. I shall send a barge immediately upon my arrival to their relief.

I feel much better today than I did yesterday. I was obliged to keep my bed nearly all day. I was so prostrated by the excitements of the night before. I find that I always suffer most from fear for others. Charley [Charles R. Ellet] is well but greatly dissatisfied with my unwillingness to gratify the men’s desire for destruction. I cannot nor will I consent to indiscriminately pillage. I cannot assume to decide that every man in the South is a rebel and entitled to have his property burned and his family murdered or made destitute.

Jimmy Roberts is with us and perfectly recovered but Granville does not get well. He is quite feeble but still stands his post and does his duty faithfully. The sickness in the fleet has greatly abated.

Tell Ellie that I have a nice side saddle for her that I will send home by the first opportunity. It was brought on board at Milliken’s Bend and handed over to our Quarter Master and I purchased it of him. She must be very careful now not to get herself thrown. Jane will be her safest horse to ride. I intend to get Willie a good shot gun for his own to send when I send the saddle to Ellie. I will not close my letter until we arrive at Helena. Goodbye my dear wife. With a great deal of love to Ma and all the others, as ever your husband in truth and love, — Alfred W. Ellet

I had closed my letter when I was startled by a shot from the Benton. We were opposite Greenville. We could see a considerable force of the enemy on a point of land, evidently intending to give us a warm reception. A few well-put in shells sent them flying without firing a gun. Colonel Woods’ forces were landed and sent in pursuit. They came within site of the rebels several times but could not catch them. They are to fleet of foot for our boys ever to catch them in a fair race. We have now left the fleet and are proceeding alone in advance to Helena. We sunk our coal barge last night and the fleet will be unable to get above Napoleon without a fresh supply which I shall send down.– A. W. E.

TRANSCRIPTION LETTER ELEVEN

Steam Ram Switzerland

Off Helena, Arkansas

August 29th 1862

Miss Ellie A. Ellet, my dear little daughter,

I have felt very lazy today, having more leisure than usual. I have been asleep several hours this afternoon. Whenever I am not busy, I think more of home than at any other time and my dear ones that I have left behind. I wrote Uncle Edward a long letter this morning but when I laid down, I gathered all the letters that I had received from home in the last three weeks and read them all over again. I often have to do this when I have been disappointed by not getting letters in proper time. Amongst the rest was your dear little letter and I concluded to answer it immediately. I write so much to your dear mother that you must not think it is neglect when I fail to answer your letters promptly. I must write to her you know and my letters are for you also.

You have heard of our late trip down the river and what we did while gone. As we were returning about ten miles above the mouth of White River, a woman was discovered waving a white cloth with the greatest energy on the shore trying to attract our attention. It was reported to me immediately by the men on the lookout and I soon made her out to be a white woman with four little children standing close around her, almost hid by the tall weeds. I ordered the boat to be put in to shore, the soldiers to put on their arms, the cannons loaded with grape to be ready for a surprise—for it was a very suspicious place—and landed. The poor woman had been there five weeks with her children alone. Her husband had left her to make his escape to our fleet when we were at Vicksburg in a skiff. She had never heard from him since and feared that he had been killed by the [guerrilla] bands on the river. They had lived almost exclusively on fish and some little food that a kind secesh neighbor had given them. I took them all on board (the oldest boy was only about Annie Ellet’s size) and sent them up to Memphis. The poor creatures could scarcely eat enough. They had hardly any clothes on and were pitiful objects to look upon. We clothed them all up, raised them quite a little sum of money, bought of the poor woman a barrel of fish oil that she had herself rendered out of catfish that she had caught, and finally sent them off feeling rich. This is only one case. I see hundreds of just such cases and always try to relieve them when in my power.

I saw a poor negro run away from his master, get in a skiff, and just from shore his master run after him and fired his gun. The poor negro dropped one oar (evidently one arm was injured) and paddled with the other. He was picked up by one of the boats behind us. I was too far off to do any good or I should have fired my cannon at the cowardly villain who shot the poor negro.

I have a nice side saddle that was captured at Milliken’s Bend. I purchased it of our Quarter Master for you. I will send it home by the first opportunity. I have also a good double barreled gun for Willie and the nicest little setter puppy that you ever saw for him. We captured a great many things and turned them all over to the Quarter Master who sells them for the benefit of the government. You would laugh yourself almost blind to see the little dog perform. Every day at meal time, he sits down by the steward’s legs and bites and growls at everybody that comes too near him and waits with his head cocked to one side for the bell to ring. The first greasy plate that changed he considers his special property and begins at the waiters leg to bite until he gets it. In the morning when the watchmen goes around to wake up the hands, Frank is on hand to help. He pulls their hair and bites their fingers and toes and noses, jumping from point to point with so much alacrity that the sleepy men don’t know where to find him. He comes to my bed and growls and pulls at the mosquito bar until he wakes me up. Indeed he goes into every room that he can get into carrying off everything that he can get hold of. He had a fine time in Mrs. Cumming’s ha__ box of collars and Capt. White’s shaving brush and apparatus. He is a great favorite but I fear he will fall overboard for he goes all over the boat, and ain’t much larger than a cat. He is very young. I want very much to get him home to Willie for he is real hunting stock and I know that you would all be pleased with him.

I hope that you are all enjoying your brother Eddie’s visit. I know that he is enjoying himself. Have you any good apples? Let me know how the orchard has borne this year and what kind of fruit. The cherries must have done right well to continue so long. How did the Lawton blackberries do? Did you have any gooseberries and currants? Tell me all these things. When your dear mother writes, she [always] has something else to write and I must look to you for all these particulars. I want to know how Jane and her colt get along—if they have kept fat or are they poor. Also tell me how White Cloud looks and everything else for you know I am interested in—everything from the chickens and ducks to the dear folks who occupy the house. I love all—everything—even the very ground upon which you all walk.

What has become of Mr. Sawyer and the Seminary? I have heard nothing of it for a long time. Tell me also what you do for your dear old Grand Ma [and] if you are able to contribute to her happiness or comfort in anyway while I am absent. I hope you will always remember that I will expect you all to take place in every way to contribute to make her happy during my absence. I am unusually well now and hope that I may continue to. I hope that John won’t have to leave you and I do not think he will.

General [Samuel R.] Curtis left here yesterday. He had captured three commanders and took them up north with him. I have now several very good girls on my boat that I would send up if I had an opportunity. They can wash and iron well at any rate and keep my clothes in first rate order. I was never allowed to wipe on the same towel twice and my sheets are changed about three times a week. I give no orders but everything is done just as nice as I could desire. I never find a mosquito under my bar. They are all brushed out and the bar let down before dark. I have a darkey who washes me two or three times a week from head to foot—fairly polishing me. So you see that I do not suffer for want of attention. I fear your mother will think that I shall be spoiled, but tell her not to fear it. I look back to our little home and see you every afternoon sitting on the porch as plainly as if I was there and wish myself one of the party as earnestly as man can wish for anything. I do not like to exercise authority and would be delighted to lay it down if the war was only ended.

And now dear Ellie, good bye. Kiss dear dear Grand Ma for father over and over again. Give my love to all the friends who remember me, to ask after me, and he seem to write to me again a good long letter, and tell Willie to do so to. If he is pleased with the present I mean to send him, he must write and let me know. Tell dear mother that I never cease to love and think of her in all my troubles and dangers. May God bless you and protect you all in their prayers of your affectionate father, — Alfred W. Ellet

TRANSCRIPTION LETTER TWELVE

Steam Ram Switzerland

Off Helena, Arkansas

August 29th 1862

My own dear wife,

Day before yesterday I received your letter of the 15th inst. with dear little Ellie’s enclosed within it. Also one from Edward of the 18th and about twenty business letters besides. I have been too busy to write since, but I think that this will be a leisure day and have commenced early this morning to write my dear wife a long letter. Yesterday I started the Lancaster under the command of Charley [Charles R. Ellet] to Vicksburg in company with the gunboat Tyler. They go to reinforce the Monarch and Bragg which were left at the mouth of Yazoo. I begin to feel very anxious about those boats—they are so far away and have not a very strong resisting force. A resolute enemy might surprise them and capture them by boarding. I gave Bartlett great caution upon this subject and I feel sure that he will do just as I directed. The captain of the Bragg I have not so much confidence in and his boat draws so much water that I greatly dread that she will get aground and thus become an easy prey to the enemy. They will have a fight before they catch Bartlett I know. I shall have to wait some time for news before my mind will feel perfectly easy about them.

I have been to see old General [Samuel R.] Curtis since my return from below and was much pleasured with my visit. He was just going out on horseback to witness a sham fight in General Osterhaus’ Division and review. He ordered a horse immediately for me and insisted upon my accompanying him on the excursion. As we rode along, I told him all about our late trip down the river—gave him all the particulars. He told me that he was going up North again and said that I must go with him to Cairo. He wanted my influence with the administration and War Department to obtain authorization to increase my river command in a way that he and I could in future work together to clean out all the little rivers while the water is so low that my present boats cannot be used. His suggestions were most excellent and he said that I could obtain authority to put it in execution—that [Admiral Charles H.] Davis was superannuated and could exert no influence whatever, and that nobody could exert the necessary influence just now but myself.

He goes up today but I cannot go with him for I have nobody of proper rank to leave in the full command. The idea as he expressed himself so flatteringly produced a thrill of pleasurable anticipation all though me. The prospect held out of again soon treading on the free soil of dear old Illinois almost made me say that I would go and let the fleet take care of itself but I soon again reflected that I dare not do it without running the risk of losing all the reputation that I have thus far gathered at such fearful risk. I thought of the telegraph and the pleasure of pressing my dear wife once more to my bosom, for if anything should call me as far north as Cairo, I will see you all, dear Ma also, if I have to have her incur the risk of such a railroad journey to see her once again. I think, however, that if I could have gone to Cairo I could have met you all at Pana.

We have had for two days a very pleasant visit from Mrs. Cowan and her husband, the Captain. Edward knows Lieut. Cowan of Captain Sparks’ Company. This was his brother and brother’s wife. Dr. Laurence married Mrs. Cowan’s sister and the visit was to him. She lives at Virden, Macoupin County. She is a very pleasant lady and you cannot imagine my dear wife how I wished that you was here also to add to our pleasant party and make me perfectly happy.

I do not expect that we shall do anything of consequence for a month to come—at least nothing that will take me away from here. I will probably send off expeditions under the command of some of my officers, but my flag ship and headquarters will remain at Helena in all probability. If you was only here now, all would be right but I dare not send for you while there is so much danger traversing the river. Scarcely a boat passes up or down that is not fired into and somebody hurt and the late accident to the Acacia, where five ladies—wives of officers of the army lost their lives—causes me to shrink from the gratification of my dearest wish, while these dangers continue to exist.

I read a long letter from Mr. Brooks from Washington. I had sent him to see Secretary Stanton upon the subject of giving me one first-class ironclad steam gunboat and ram to be added to my fleet. His interview with the Secretary was most gratifying. The ram fleet and its commander has his entire confidence. He told Mr. Brooks that he feared that he did not have the authority as matters now stood but would consult with the Judge Advocate and if there was no difficulty in the way, he would give me a carte blanche to fit up a fleet to suit myself, and one that I would not be ashamed of. He told Mr. Brooks while speaking upon the subject of punishment of my unruly men that he would sustain Colonel Ellet in whatever he found it necessary to do. I feel very proud of all this confidence and will do my very utmost to continue to deserve it but I am tied the tighter by this unlimited trust and will be kept all the time more closely confined because I cannot risk such a reputation in anyone else’s keeping.

Captain Brooks also had a talk with Secretary Stanton about our share of prize money for captures made and the enemy’s fleet destroyed before Memphis and elsewhere. Mr. Stanton said that this was an entirely new question of prize money to the army, that he knew that we had greater claims on the prizes than the gunboats had, but supposed that they would appropriate them. That he would look into it, however, and see that our interest was not neglected. I have a powerful friend in Stanton, but he is so overwhelmed with duties that he may overlook many things of importance to me and my fleet just because he has not time to think of it. He told Mr. Brooks that I must act upon my judgment and if I committed errors that he would sustain me.

I am very well and all of those in whom you are particularly interested excepting Gran[ville] who continues miserable. I would send him up home but I have lately adopted a rule not to furlough anymore and if I were to break it in Granville’s case, I should be charged with inconsistency and partiality. Just now I think I stand well with all the soldiers and men of any worth in my fleet and I intend to try to pressure their confidence and good opinion. I will endeavor to find some business that I can send Gran[ville] to execute that will meet the case. He will not leave his position and has never yet neglected his engine, even when he should have been in bed. I have become greatly attached to the boy for he is in every respect so different from what I had always considered him to be.

I have just got rid of Captain Porter of the Sampson who has been a great source of annoyance to me being a perfectly worthless scoundrel and when out of my sight I could not count on him for a moment. I started him in a hurry yesterday and have put Sergeant Southerland as captain on the boats. I find my soldiers I can rely upon to the death. You never saw any greater devotion than they exhibit. They do have I know unlimited confidence in, and attachment to me, and I believe there is not one among them who would hesitate to go with me into the very jaws of death without my asking him. I am building up of such men a strong power around me, and think that before long I shall get my fleet to command, that I shall be able to feel that each boat will do her duty when called upon. This will relieve me from the necessity that you my dear wife so much object to my always being myself foremost in danger hours. My men begin to complain that I always take the risk upon myself and give them no opportunity for distinction, but I have been obliged to do this. I had to convince them all that I feared nothing for myself so much as the failure to do my duty and they now respect me for my courage, and are loud in their urgent request to be permitted to win reputation and honor likewise. Hereafter, I shall not lead every dangerous expedition myself, but will direct and entrust the execution to my officers, having now four of such men as I can rely upon obeying my every instruction and exerting themselves for the credit of the fleet. 1st, Charley [Charles R. Ellet], who for the present I have placed in command of the Lancaster, and you may be assured that any man who has the temerity to refuse to go into a dangerous place when Charley orders him will find more to apprehend from him than any enemy that may be in advance. 2nd, Bartlett. He understands me fully and is always proud to execute my orders to the letter. 3rd, Lieutenant Hunter on the Queen [of the West]. There is no discount on him, I can assure you. And Sergeant Southerland on the Sampson, and Switzerland under my own charge gives me a right formidable and efficient fleet.

Today the river has been full of wounded men in the most terrible state of decomposition. They are the victims from off the Acacia recently snagged above here. No one stops them. They are allowed to float past and become food for fish. Yesterday morning four bodies were found lying against our coal barge. The negros in charge of the barge pushed them off and reported about it afterwards. The mail boat is said to be coming. I must close with much love to all [and] to dear Ma in particular. Tell Edward to hire for me three or four good carpenters, Ph____y for one, if he can get them. I will give them from forty to sixty dollars per month according to their value. I want also five or six No 1. Pilots and will give $225 per month. I do not think that John can be taken from you as he is the only male of your household. I think the law reserves to each household one man. The boat is here, must close. — Alfred W. Ellet

Hello,

Brig. Gen. Alfred Washington Ellet was the great-great grandfather of my dear friend and neighbor, Ned Ellet, in El Dorado, Kansas.

I was absolutely thrilled to see his letters you posted on your blog – ones written to his wife during the Civil War. Could you tell me where these letters are archived?

Thank you so much. Feel free to call or email me:

316-323-3928

smilbourn@gmail.com

LikeLike