This letter was written by 35 year-old constable William F. Chapple (1826-1900), the son of Samuel Chapple (1783-1833) and Sarah Dinsmore (1787-1876) of Marblehead—later Salem, Massachusetts. Swept up in the patriotic fervor after the firing on Fort Sumter, William rushed to enlist as a private in Co. I, 8th Massachusetts Infantry, a 90-day regiment—naively thought to be more than adequate time to put down the rebellion. The 8th Massachusetts did little more than guard duty and protect the railroad during their brief history.

Though William yearned to “go into Virginia where we can see the elephant,” as he put it, that would have to wait until he reenlisted in October 1861 into the 23rd Massachusetts Infantry, Co. F. In the 23rd Massachusetts, William was promoted from a private to a corporal and performed duty in the commissary. William and his dog “Curly” are mentioned in the regimental history on pp. 31-32 while on the sea voyage to the North Carolina coast: “Towards dark a fresh gale from the southwest arose and so hindered us that it was decided to cast off the hawser. All hands, but enough to work ship, were ordered below, and, then, as we stood off and on, ensued scenes which, though not without their laughable side, may perhaps best be left to the memories of the participants. One of these was provided by Commissary Chappie’s spaniel as ‘sick as a dog’ in her master’s bunk. ‘Curly,’ the pet of Company F, if not of the regiment, was conspicuous with her red blanket on the march through Boston and New York. Her pups, born on the eve of the battle at Roanoke Island, were in great demand as souvenirs of that affair.”

[Note: This letter is from the personal collection of Jim Doncaster and is published by express consent.]

TRANSCRIPTION

Co. I, 8th [Massachusetts] Regt.

Baltimore, Maryland

July 2, 1861

Friend Weed,

I take the liberty to write to you knowing that you would like to know of our whereabouts. I am well. I hope you are enjoying yourself and are blessed with the best of health.

We got orders six days ago at 2 o’clock P. M. to pack up some of our things for a march. We of course knew not where we were a going. We got ready in a short time. We put 40 rounds of cartridges in our boxes. We were then ready and willing to face anything that came in our way, We got into line and in a short time the clouds began to look black and wild. We were ordered back to our tents by our Colonel. We hardly had time to get to them before it began to rain and blow. I have not seen such a blow for many a day. We had to hold on to the tent poles to keep our little cloth houses from blowing over the hills. It lasted about one hour, Just as we got into a line before the blow, we had the pleasure of seeing Mr. Giswin Bates, Phippen, & Lee coming up the hill. They with us struck a B-line for the tents.

The Regiments were soon again into a line. There was only one half of the Eighth and that half was the right wing of the company. [The companies] that compose the right wing are 2 of the Marblehead, the Beverly, Gloucester, and the Salem [company]. The other 5 companies stopped at the Relay [House] to take care of the railroad and other things. The whole of the Sixth Regiment started with us. We got on board the cars. There was 26 of them full. The old traveling cooking stove puffed away and we fetched up on the outskirts of one of the most miserable dens of iniquity that can be known by the name of Baltimore. We got out of the cars and marched some distance and halted at a place called Mount Clare Station. There is a great number of troops all about here encamped. The guard was posted and everything now was ready for supper which we got. It consisted of 2 slices of dry bread and a mug of water. It was dark by the time we got through and we turned into the grass for the night—all but those who were on guard. It rained in the night and it was cold. We got wet for we had not tents to cover us from the storm. All we had was our blankets to cover us. We had to lay and face the music.

In the morning we started nearer the City. We fetched up in a grove called Stewart Park. Stewart with his two sons are in the Southern army. The old scamp is a general. ¹ The park is at the foot of his late residence. His house is closed up, It has rained 2 days and nights and we were a prepy-looking set of pups, drenched to the skin. Some say we are to stop here. If we are, I should think they would let us have our tents. It is now dinner time and I must stop for a few minutes to eat it. Won’t take but a few minutes to eat what we have got to eat. I will now tell you what we had for dinner—dry bread, onions in the bunch. They are a good deal better for that and pickles. If they would be good enough to give us vinegar to put on our onions, we could make a good meal, and we had water to wash it down with. It is rather hard but I suppose it is fare, and hard at that. The old saying is put your trust in God and keep your powder dry. we do that and we put our trust in Thanksgiving day that I hope we shall see. I suppose the reason why we fare so hard now is because all our things is at the Relay.

Day before yesterday our Colonel had the offer of a vacated house which is near here. He accepted it and now we are in a house. This house has been a sporting place so they say. In the yard there is a iron target for practice. We do not like to be cooped up here. It is the worst place that we have been in. I had rather get wet everyday in the week that to stay in this place. We are now separate from the Sixth Regiment. They have gone somewhere else. There is a great many secessionish here. We have marched through the City a number of times. Night before last we got the alarm of the firing at the Depot. We were in readiness to start at a moment’s notice. After waiting about one hour, we were ordered to turn in. Yesterday A. P. Brown & Capt. Silver came into camp. Capt. Silver was at the Relay when we were there. James Gillis has been at the Relay.

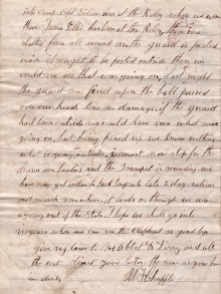

There is a slatted fence all around us. The guard is posted inside. It ought to be posted outside. Then we could see all that was going on. Last night the guard was fired upon—the ball passed over our heads [but] done no damage. If the guard had been outside, we could have seen what was going on, but being penned up, we know nothing what is going on outside.

I must now stop for the drums are beating and the trumpet is sounding. We have now got orders to pack knapsacks, take two days rations, and march somewhere. It looks as though we were agoing out of the State. I hope we shall go into Virginia where we can see the elephant. So goodbye.

Give my love to Mr. Abbot & Direy and all the rest. Direct your letter the same as you have been doing. — W. F. Chapple

¹ The property belonged to George H. Steuart (1828-1903) who was a captain in the U. S. Army before the Civil War but resigned his commission to join the Confederacy as a Brigadier General. The home was on Maryland Square in the western outskirts of Baltimore. It was confiscated by the U. S. government and used as a campground. By February 1862 it was known as “Camp Andrew” named after Massachusetts Governor John Andrew. It consisted of about 36 acres. In May 1862 the property was taken into the control of the medical director of the U. S. Army and the former mansion was turned into the administration building for a hospital that was constructed on the grounds named “Jarvis Hospital.”