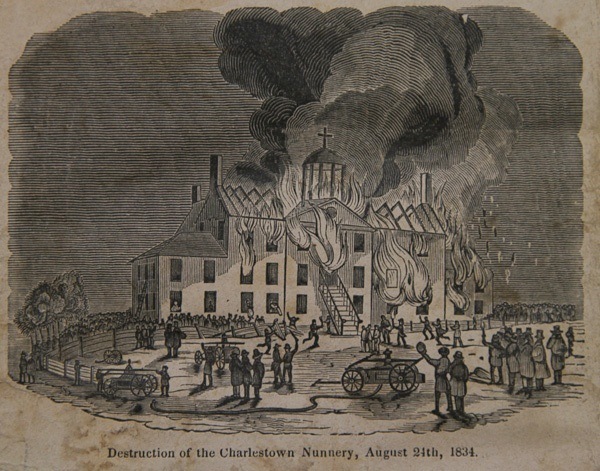

This single sheet of paper, written on both sides, contains the cryptic statements of at least three eyewitnesses to the Ursuline Convent Riot in Somerville, near Charlestown, Massachusetts—one of the saddest chapters in our American history. On a warm night in August 1834, some 50 or more Protestant, Know-Nothing supporters, whipped up by false stories circulating about young women being held against their will at the Catholic convent, gathered together and assailed the convent and started fires. As the conflagration made headway, it was noticed that many responding firefighters stood by and refused to attack the fire, many of their members having friends or relatives in the mob. The following account was supplied by one of the mob participants:

“The first thing that was done, after getting in, was to throw the pianos, of which nine were found, out of the windows. The mob crowded in in such numbers that it was with great difficulty that I got upstairs to the chapel, which was located on the second floor. When I finally succeeded in forcing my way into the chapel I found a fire about the size of a bushel-basket blazing merrily in the middle of the floor. It was made of paper, old books, and such other inflammable stuff as they could lay their hands on, and soon spread in all directions. When the main building was enveloped in flames we went for the cook-house and ice-house, which were separate buildings, and set them on fire.”

“In the immediate aftermath of the fire and riot, officials made the expected response. The mayor of Boston condemned the incident. Officials in Charlestown tried to deflect blame on the neighboring city of Boston, whose inhabitants had certainly taken part in the rampage. The governor of Massachusetts offered up a $500 reward for information leading to the conviction of the rioters.

And the finger pointing began. Why had the firefighters not aggressively put it out? Did they fear the violent Know Nothing mob flinging furniture out of windows at anyone below? Or had firefighters actually participated in sacking the convent, as many said? Why had the selectmen not done more to extinguish the rumors? And why did the Know Nothing rioters freely parade the day after the fire in celebration of their actions?” [New England Historical Society]

A committee of investigation was launched immediately after the affair and these notes may have been gathered by one of the members of the committee.

TRANSCRIPTION

August 14, 1834

Statement made by Tapley, Chief Engineer

At the first alarm of fire on arriving found fence on fire and a bonfire. The fire departments were there. No. 13 Boston Engine was there. Requested them to return home but they did not. Went to fetch [Edward] Cutter. ¹ Saw 10 or 15 men run toward the Convent. Saw Mr. Babcock.

Went to the Convent when found to be on fire. Went round the building. Saw several squads of people. Thot it not safe to order the Engines to play knowing it to be impossible to save the building. Kept 2 Engines there to keep fire from spreading. Saw a number with caps. Looked as if f___ ____’s men appeared to be willing to play on the fire. Saw Col. [Thomas C.] Amory ² but had no conversation with him. Did not think had strength sufficient to extinguish the fire. Thinks the mob consisted of 1200 people.

Mr. Tyler says that Chief Engineer ordered him to the [Middlesex] Canal to form a line for water but found it impracticable. Thot it not safe to play on the fire by reason of the mob.

Capt. [James] Deblois (Assistant Engineer) states that he went at first orders. When No. 13 first went up the hill, told him not to go up there. Was no fire, but they answered “Go ahead.” Saw them take off badges. Saw Col. Amory who ordered a lane to be formed [but] order not obeyed. Some person said better not bring Engines here without you want them broken to pieces.

¹ Edward Cutter was a member of the Massachusetts legislature and owner of a nearby brickyard.

² Thomas C. Amory was the Chief Engineer of the Boston Fire Department.